In an effort to clear-up a longstanding question in the community, here is my answer to “how does one detect Sephardic ancestry?”, for example, in the results of an autosomal test. Thanks to my collaborator Dolev Revivo for all his help getting caught up on and creating new Sephardic stories!

This is a long post, but it will not be a perfect or complete answer, and I hope to continue to add to the information here in future posts. I encourage folks to comment any questions or thoughts they have so that these can be included in future work.

Summary of covered content:

- Definitions of Sephardic Jews, autosomal ancestry, and how the “Ashkenazi” component in ancestry tests actually works

- Why there cannot yet be a “Sephardic” component in ancestry tests that works the same as the “Ashkenazi” ones

- Review and analysis of autosomal ancestry tests for Sephardic and non-Sephardic Jews from FamilyTreeDNA, MyHeritage, AncestryDNA, and 23andMe

- Suggestion of the communities where real Sephardic ancestry peaks today, and a description of the ancestry of Eastern Sephardic Jews

To begin, we must first set out shared definitions of key terms and concepts. What does Sephardic mean here? What is autosomal ancestry in the first place, and how can it be detected in a test? If there are components defined by Ashkenazi ancestry, why aren’t there components defined by Sephardic ancestry?

- The term Sephardic Jews is defined here as corresponding to the network of communities of Jews of medieval Al-Andalus and the succeeding Christian kingdoms of Iberia that existed from around the 9th century until the late 15th century. Ancestry from these Jews means descendance from actual people who left this original region of settlement, plausibly in one of the mass movements in the late 14th or 15th centuries. This definition does not include those Jews who follow the Sephardic rite of Judaism but do not have actual ancestry from those that developed that rite.

- Autosomal ancestry refers to most of one’s ancestry, deriving from one’s 22 pairs of non-sex chromosomes. What’s relevant here is how the autosome can be used to deduce ancestry, and for that there are two major factors to consider. Throughout the autosome, there are tiny mutations called SNPs, and there are potentially millions of them to consider. Many of these SNPs do not correlate well with recent ancestry differences between humans, but many do, and these are a primary source for the data that goes into the ancestry composition reports that companies like AncestryDNA, 23andMe, FamilyTreeDNA, and MyHeritage provide. The second factor is that these SNPs that are informative for recent ancestry are often structured into segments which we can describe as identical-by-descent. It is thus the same kind of science as cousin matching, just applied at a different scale and in a different context. Companies like 23andMe use a proprietary algorithm applied to these diagnostic SNPs within the IBD segments shared between the sample provider and their reference populations to create their Ancestry Composition report.

- When a company claims to have detected Ashkenazi ancestry in someone’s genome, odds are they found IBD segments shared between the sample provider and their Ashkenazi reference population, totaling the length of each segment together to arrive at a total % Ashkenazi. The ubiquity of Ashkenazi references in these tests is in large part due to the fact that Ashkenazim have a lot of population structure, which is to say, systematic differences between Ashkenazi Jews and all other populations that arose due to their unique history and ancestry. What’s relevant here is that Ashkenazi genomes tend to be quite similar, by way of Ashkenazi Jews sharing a lot of IBD segments with each other. This phenomenon is often termed or explained by “endogamy”- that is to say, the historical and cultural trend for Jews to marry within their own communities. This is partially correct but obscures a greater truth. Yes, these IBD segments have been preserved to the modern day by way of endogamy, but endogamy alone is not the cause of this relative excess of sharing. In large part, these IBD segments that exist at the scale of the whole population can be dated back to the massive expansion of the Ashkenazi population between the 14th and 17th centuries, and before that still, to the very founding of the first Ashkenazi communities in Central Europe back in the 9th-11th centuries. Thesefounder events are, in fact, the original causes of the resultant effect that we in the Jewish genetic genealogy community often call “endogamy”.

Given all this, why is there no Sephardic reference population at companies like AncestryDNA or 23andMe? Also, why are the Sephardic Jewish components at FamilyTreeDNA and MyHeritage not nearly as relevant for our definition of Sephardic ancestry as the Ashkenazi component is for Ashkenazi ancestry? And without a dedicated component, how can we tell whether one has Sephardic ancestry at all?

To properly answer these questions, I feel it’s necessary to break up the complexity by eras and regions. After all, without any ancient Sephardic genomes, we’re left to do our best with what we know from history and what we can glean from modern populations claiming Sephardic ancestry.

The event horizon: unknown pre-expulsion Sephardic Jewish population structure

To properly summarize what’s known about Sephardic history from the founding period to the expulsions and what inferences we can make about their population structure, is beyond the scope of this post. But in essence, what’s important to understand is that unlike with Ashkenazi Jews, who almost entirely descend from– and have by way of endogamy preserved– the ancestry of their late medieval ancestors, most modern Sephardic Jews have a fundamentally different connection with their namesake-ancestors.

As stated above, Sepharad as a distinct Jewish community existed for around 600 years, with the first references to Jewish communities in Al-Andalus coming from the 9th century. It is truthfully unknown exactly where the ancestors of these early Sephardic Jews came from or how long they’d been in Iberia. Many scholars have claimed that there existed a large community of Jews in pre-Islamic Visigothic Iberia which represent their ancestors, but other scholars have claimed the opposite, often with the implication of roots in North African Jewry. What’s clear is that the earliest Sephardic Jews we know of in the historical record were something of a new kind, with their densest early settlement being located in Andalusia and in the Ebro Valley. We also have hints that not all Jews in the Iberian peninsula had the same kind of Jewish culture– in Catalonia, outside of the territory of Islamic Al-Andalus, Jewish settlement was of a slightly different character.

Starting from the 9th century, we begin to see more and more Jewish communities established in Iberia. Importantly, we see Jewish communities arise in urban and rural areas, in areas controlled by Muslims and by Christians, with Jews working in trade, in manufacturing, even in agriculture. Eventually, though, their niche began to disappear, and in 1391 a major expulsion removed a large portion of Jews from Iberia. These refugees fled especially from the provinces controlled by the Kingdom of Aragon in the north and east. Nearly one hundred years later, in the almost too-famous 1492 expulsion, Jews were forced to leave the Kingdom of Castille, most of whom fled to Portugal where they were expelled in 1497.

Sephardic Jews after the expulsions by-in-large arrived in areas where there were already Jewish communities that were not Sephardic themselves, and subsequently mixed with these non-Sephardic Jews. Most Sephardic Jews fled to western North Africa (Morocco & Algeria) or to the Ottoman Empire (especially modern-day Greece and Turkey) or to Italy (the north and center, as the south was under Aragonese control). In all of these places, new communities were formed, and while the cultural understanding of themselves as “being from Spain” became widespread, the people’s genomes changed significantly. To conclude, we cannot simply use a collection of modern Sephardim from across the Mediterranean to make a “Sephardic Jewish” component and have it work the same as the Ashkenazi one, for a few fundamental reasons:

- There may never have been a strong founder event at the beginning of Sephardic history, and without more recent population expansions (without admixture), it can be difficult to determine what is a “Sephardic” segment.

- The multiple regional origins of Iberian Jewish refugees, for example between Jews from Portugal, Andalusia, Extremadura, and Castille, and Jews from Aragon and Catalonia. There may have been differences between the communities in these regions that would have compounded as early modern Sephardic diaspora communities formed.

- Modern Jews with mixed Sephardic and non-Sephardic ancestry would obscure the IBD networking that is fundamental to accurate component scores in many of these tests.

- The communities that Sephardim mixed with were possibly related to the original Sephardic communities in unbalanced and uncharacterized ways, further obscuring the picture and requiring us to assume a lot if we attempt to estimate their ancestry.

Our starting point: actual results from multiple communities at multiple companies

Here I’ll consider results of autosomal ancestry tests from four different companies: 23andMe, AncestryDNA, FamilyTreeDNA, and MyHeritage. I’ll look at results from individuals hailing from many different edot, that is, different Jewish communities. These will include communities that are known to have significant Sephardic ancestry, such as Moroccan Jews and Turkish Jews, as well as smaller communities in North Africa and the former Ottoman Empire. In addition, I’ll compare the results with a control population, the local Jews of the central Maghreb who by-in-large do not descend from Sephardic Jews. At each step, we must reckon with complexities in the histories of each community as well as the technical details of the tests and their results.

Two companies– FamilyTreeDNA (FTDNA) and MyHeritage (MH)– have named a component in their test after Sephardic Jews. Both companies are also marked by other unique features, relative to AncestryDNA and 23andMe. For example, outside individuals can upload their autosomes to FTDNA and MH to get their own ancestry results. Thus, some of the results considered here were originally tested at FTDNA and MH labs, while others originate from different companies. This contributes to the pattern of a high degree of variance between individual results. However, this pattern extends well beyond the scope of raw data, where these companies do put out individual reports that are functionally impossible. Caution and a sample size to work with are necessary to make sense of their results!

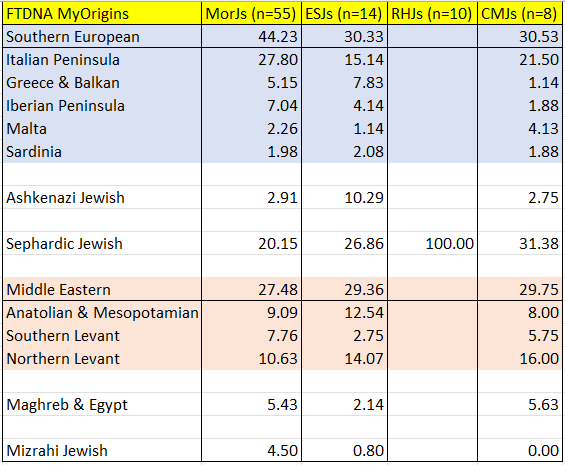

Here I report averages of four populations’ results in FTDNA’s MyOrigins report. MorJs corresponds to Moroccan Jews, ESJs corresponds to Eastern Sephardic Jews, RHJs corresponds to the Jews of Rhodes (technically a subset of ESJs), while CMJs corresponds to Central Maghrebi Jews from eastern Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya. High variance exists at the level of individual results, but from this perspective we can see that these populations tend to be different in a few systematic and informative ways. One complicating factor is that trace ancestries on FTDNA are put in a non-integer format (e.g. <2% or <1%). I normalized these by just taking the integer as written and not including those components that remained under 1% after averaging, except for the Mizrahi Jewish component in ESJs.

First, let’s focus in on the Sephardic Jewish component. Moroccan Jews score an average of 20%, Eastern Sephardim an average of 27%, and Central Maghrebi Jews an average of 31%. This here is an historically impossible result, assuming the so-named Sephardic Jewish component actually represented Sephardic ancestry. Real Sephardic Jews fled to specific locations in the Mediterranean, and Morocco was by far the most common destination. While the city of Tunis received many Italian Jewish immigrants with Sephardic ancestry– especially from Livorno– these people organized themselves into a community separate from the local Twansa. These local Jews descend from Jews who had resided in the Maghreb for centuries and did not mix much with the Sephardic exiles, mostly because they simply did not arrive in large numbers throughout most of the central Maghreb. While in modern-day Israel, the term “Sephardic” is often applied to these Maghrebim, they are not actually Sephardic by ancestry, and their result here helps to show how this component actually fails in being able to imply real Sephardic ancestry.

The fourth population considered here, a subset of Eastern Sephardim, is represented by the Jewish community of Rhodes, a city and island of modern-day Greece off the coast of modern-day Turkey. I found the results of ten Rhodian Jews, and every single one gets 100% Sephardic Jewish! Does this mean that this community of Jews is completely descendant from Sephardic exiles?? Of course not! Rhodian Jews are in fact just the basis of the reference population for a component that FTDNA calls “Sephardic Jewish”. And while they surely have significant ancestry from real Sephardic Jews, Rhodian Jews (like all ESJs) are a mix of different Jewish communities that merged and mixed in the Ottoman Empire. See below for more discussion regarding this point.

What about the other components? Well, I must stress again that MyOrigins results are highly variable between individuals of the same population, and that is realized by a high standard deviation for each of these averaged scores (curiously, except for the Sephardic Jewish component, which is more stable). For example, while Italian Peninsula’s average score is around 28% in Moroccan Jews, the range extends all the way from 0% to 60%, with a standard deviation of almost 18%! Okay, so, given these averages and this variance, what can we take away? Here’s what I see:

- Moroccan Jews are on average more “European” than ESJs and CMJs, most evident in their Southern Italy and Iberian Peninsula scores.

- ESJs have much more Ashkenazi ancestry on average than Moroccan Jews and CMJs.

- All have roughly equal amounts of Middle Eastern ancestry, with a lot of variance within and between populations for the preferred component.

- Moroccan Jews and CMJs have more North African ancestry than ESJs, on average.

We’ll see if these average differences repeat with the other companies’ results. Sadly, though, you can’t view the ancestry results of matches on MyHeritage, which makes gathering individual results to make a sample quite difficult. However, in the few I was able to find from the communities under review here, there’s enough information to make some sense of their “Sephardic Jewish – North Africa” (SJNA) component with some notes on the other components scored. Between the handful of Turkish Jews I found, the averaged score for the SJNA component was 28%. In the single Moroccan Jewish result I was shared, the result was quite different- almost 84%. In the single Tunisian Jewish result I was shared, the scores for SJNA were even higher, at 88% (23andMe raw data) and 92% (AncestryDNA raw data). These scores lead me to believe that MyHeritage has both Moroccan Jews and Tunisian Jews in their “Sephardic Jewish – North Africa” reference– even though the latter are not even Sephardic.

What other components are scored by these individuals on MyHeritage? For the North African Jews, outside of the score of their own component, it’s a mix of trace ancestries including Greek and Southern Italian, North African, and West Asian. For the Turkish Jews, significant scores included elevated Ashkenazi (average of 22%), Greek and Southern Italian & Italian scores (combined average of 29%), and Middle Eastern & West Asian scores (combined average of 12%). We can see the consistency of an Italian source for the southern European ancestry being preferred over Iberian (which is still sometimes scored) and for Eastern Sephardim to have much higher Ashkenazi scores than these other Jews.

Before moving onto AncestryDNA and 23andMe, I want to zoom in on the results of two individuals we have from FTDNA and MH. These two individuals have ancestry from the northern-most region of Morocco– what is today called Tanger-Tetouan-Al Hoceima– is a place with a special Jewish culture for our purposes here. It is the only region in Morocco that preserved a “Spanish Jewish” culture and tradition, speaking Haketia, a language related to but distinct from the more well-known Ladino. If there’s any community that stands a good chance to be mostly descendant from Sephardic exiles AND large enough to have some genetic results online, it’s them. Let’s take a look!

On FTDNA’s MyOrigins, these Tetouani Jews score the same as other Moroccan Jews in the Sephardic Jewish component, which again is based on modern Jews from Rhodes. Other components differ more significantly, with a higher Iberian Peninsula score (average of 10.5% vs the MorJ average of 7.0%) and a higher Ashkenazi Jewish score (average of 6% vs the MorJ average of 2.9%). These results may imply that an elevated Iberian score and an Ashkenazi score lower than ESJs but higher than the average Moroccan Jew means higher actual Sephardic ancestry.

In MyHeritage’s report, the Tetouani Jews have even more interesting and potentially informative scores. Unlike most North African Jews, who score 80-90%+ of the Sephardic Jewish – North Africa component (likely based on different North African Jews themselves), Tetouani Jews score similarly to Turkish Jews, with an average of only 26% in that component! This result tracks with the much smaller match lists they have relative to most other Moroccan Jews, who similar to Ashkenazi Jews will match other Moroccan Jews from all over the country due to an excess in IBD sharing. They also score elevated Iberian (average of 16.9%), Ashkenazi Jewish (average of 9.5%), Sardinian (average of 16.3%), and North African (average of 11.8%), relative to the other results I’ve seen. These Tetouani Jewish results help us to see that detecting Sephardic ancestry is complicated but not indescribable, and I’ll talk more about them when we get to 23andMe results.

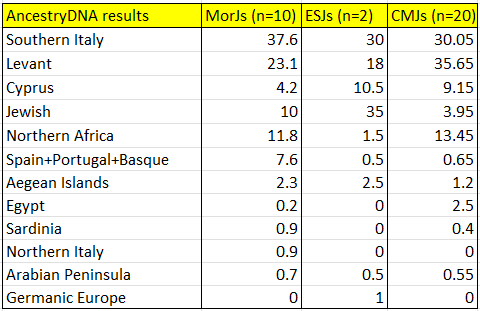

The results of Moroccan Jews, Central Maghrebi Jews, and two Turkish Jews from AncestryDNA track with the emerging patterns from the review of other companies’ results above. Here, though, there is no component that is based on individuals with some Sephardic ancestry. Sadly, I was only able to find two ESJ results- both from Turkey- but here’s what jumps out to me:

The results of Moroccan Jews, Central Maghrebi Jews, and two Turkish Jews from AncestryDNA track with the emerging patterns from the review of other companies’ results above. Here, though, there is no component that is based on individuals with some Sephardic ancestry. Sadly, I was only able to find two ESJ results- both from Turkey- but here’s what jumps out to me:

- Southern Italian is again the preferred primary source for these different Jewish communities’ European ancestry. Curiously, it’s again in Moroccan Jews where this component peaks.

- The “Jewish” component here- defined by Ashkenazi Jews- again peaks significantly in Turkish Jews, is found at elevated rates among Moroccan Jews, but is almost a trace ancestry among central Maghrebi Jews.

- The Levant component is the preferred Middle Eastern source for everyone, but varies widely between (and to some extent within) each population.

- North African ancestry peaks in central Maghrebi Jews and in Moroccan Jews, while is just a trace ancestry in Turkish Jews.

- Iberian ancestry (here the sum of the Spain, Portugal, and Basque components) peaks in Moroccan Jews and is barely found in ESJs or in CMJs.

- The Cyprus component is lower on average in Moroccan Jews than in ESJs and CMJs, but those scores are highly variable and it may not be that informative.

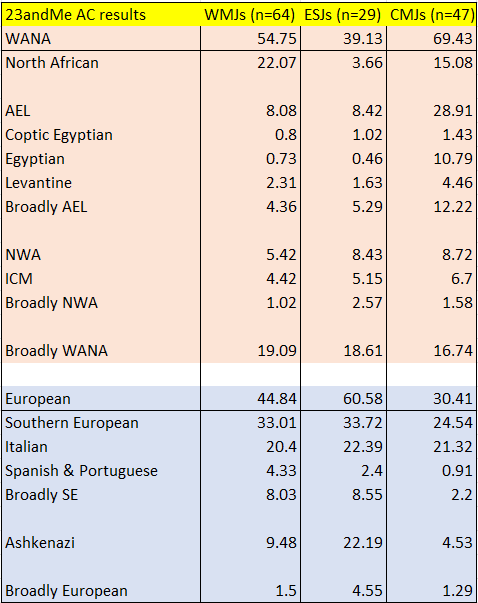

Finally, let’s check out the 23andMe results, for which I gathered the largest sample sizes for each population so far. Western Maghrebi Jews (MWJs) here denotes both Moroccan Jews and Algerian Jews, who by-in-large are closely related. Again, ESJs corresponds to Eastern Sephardic Jews and CMJs corresponds to Central Maghrebi Jews.

Finally, let’s check out the 23andMe results, for which I gathered the largest sample sizes for each population so far. Western Maghrebi Jews (MWJs) here denotes both Moroccan Jews and Algerian Jews, who by-in-large are closely related. Again, ESJs corresponds to Eastern Sephardic Jews and CMJs corresponds to Central Maghrebi Jews.

23andMe results are unique in part because the components are structured differently; here, most components fit into an upper or broader category. For example, one of these categories is abbreviated as “WANA”, meaning Western Asian & North African, and it includes a North African component, broad components like “Arabian, Egyptian, and Levantine” and “Northwest Asian” which themselves include sub-components, and even a Broadly WANA component which always includes a substantial portion of these Jews’ total WANA ancestry. This system makes sense as it acknowledges that all components are related to each other and some are more related than others. But it requires a slightly different interpretation, relative to the other companies considered here.

The North African component easily distinguishes Eastern Sephardim (including Turkish Jews, Greek Jews, Bulgarian Jews, and one Bosnian Jew) from the two main kinds of North African Jews, with their average score of just 3.7%. However, unlike previous estimates, in this test Jews from the Western Maghreb have elevated scores (22%) on average of the North African component, versus those from the Central Maghreb (15%).

A look at the AEL component in CMJs, especially in the Egyptian and Broadly AEL sub-components, may reveal a reason for this new discrepancy. These Tunisian Jews, Djerban Jews, and Libyan Jews on average score significantly higher in these components, plausibly in part due to the clinal differences between respective North African host populations. This also speaks to the difference between the two North African Jewish clusters, who are often assumed to be related, while population genetics has revealed a significant amount of substructure between the groups.

Again, here we see that the Ashkenazi component is useful in distinguishing between these different populations. ESJs have a good chunk of their total ancestry assigned to it (average of 22%), and while WMJs have a lower average rate (9.5%), it’s still more than double the average coming from CMJs (4.5%). The fact that even these Jews from the Central Maghreb score that much shouldn’t be taken for granted– this represents evidence of IBD segment sharing between Mediterranean Jews who definitely do not have real Ashkenazi ancestry, and Ashkenazim themselves, helping to nest AJs as being a part of the broader historical and genetic network of “Western Jews”.

Cross-company consistency continues with the Southern European scores. For each population, the “Italian” component is again the primary source, being scored similarly (20-22%) across the three populations considered. The Spanish & Portuguese component again peaks in Western Maghrebim at an average of 4.3%. Compare with Central Maghrebim, who score under 1% on average (0.9%), and with Eastern Sephardim who score between these two populations (2.4% on average).

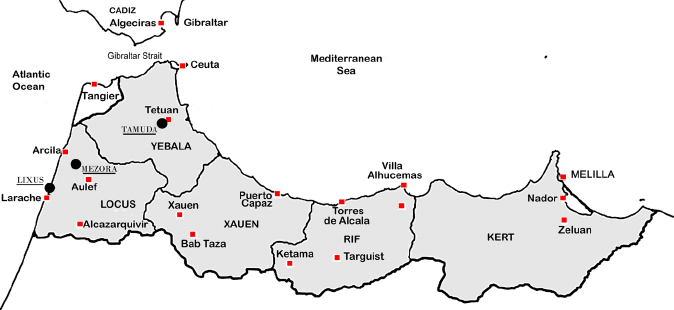

Within my WMJ cohort there are nine individuals who on their profile claim to have ancestry from the zone in northern Morocco where the Haketia-speaking, ostensibly “Spanish Jewish” culture was located. These include the cities of Tetouan, Larache, Melilla, and Gibraltar, which was settled by Jews from this northern region a few centuries ago. Intriguingly, their Spanish & Portuguese scores (average of 4.7%) are very similar to the WMJ average (4.3%), but their results differ on average from the total WMJ cohort on a few components:

- Their average North African score (19%) is lower than the WMJ average (22%)

- Their average Italian score (17.2%) is lower than the WMJ average (20.4%)

- Their average Ashkenazi score (11.6%) was higher than the WMJ average (9.5%)

The one individual from Gibraltar differs on informative components even more significantly. They score just 9.8% North African, 10.6% Spanish & Portuguese, and 16.6% Ashkenazi! While it’s possible they have some ancestry from Italian Jews which among other things could inflate their Ashkenazi score, it’s difficult for me to point to a result that’s more likely to be from someone with more actual Sephardic exile ancestry.

The map was taken from The Archaeology of the Spanish Protectorate of Morocco by Margarita Diaz-Andreu.

Final thoughts: Sephardic ancestry as it came to exist today

It’s said that in history, there are winners and there are losers. For the Iberian Jewish refugees given impossible choices in 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries, I’m sure they felt more like the losers of history. Nevertheless, in the sense of historical success as “being remembered”, I’d venture to say the expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492 is about as successful as an event can get. This expulsion captures the imagination and becomes a useful narrative for the understanding of one’s origins. Indeed, Sephardim were able to establish new communities in most of the places they arrived, and were able to preserve and extend the practice of their rite across the Mediterranean and beyond, even going as far as the Jewish community in Bukhara. Their success contributes to the confusion surrounding the term “Sephardic” in Israel today and in the understandings (and misunderstandings) that modern Sephardic Jews have about their ancestry. For an insight into the real lived experience of the generations immediately following the Sephardic exile, I recommend checking out this chapter, freely available online, by Mercedes Garcia-Arenal titled The Jews of Fez through the Trial by Inquisition of the Almosninos.

The original inspiration for this post was related to Sephardic ancestry in the Balkans and more generally in the realm on the former Ottoman Empire. As we’ve seen with the scores of Eastern Sephardim above, significant proportions of total ancestry are assigned to the Ashkenazi component. For individuals from these communities, whose cultural and religious identity is almost always “Sephardic”, receiving these results can often be quite confusing. I’ll conclude this post with a brief description of the ancestry of the Jews of the Ottoman Empire, leaving the stories of North African Sephardim and non-Sephardic Jews for another day.

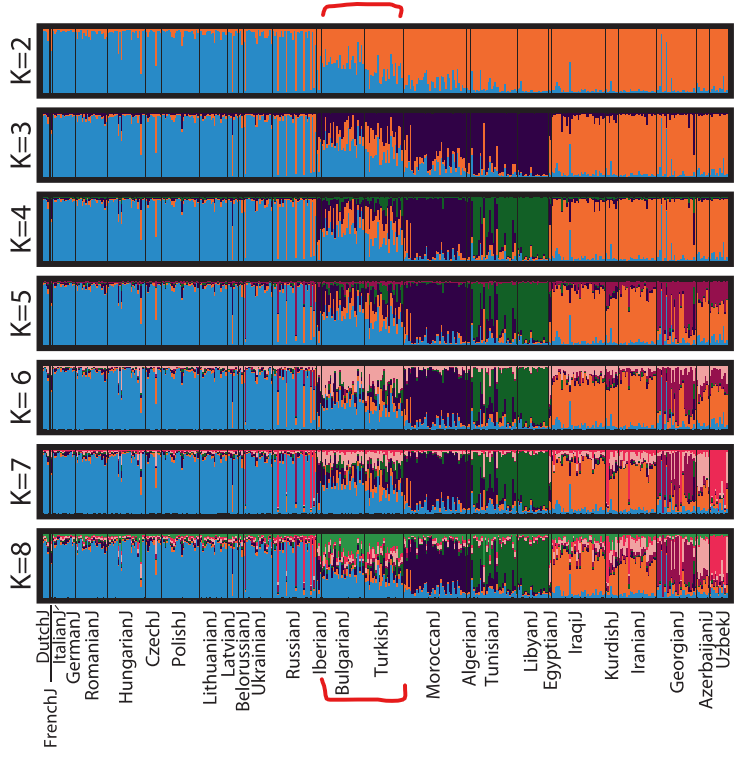

First, I want to share a graphic from the population genetics study Kopelman et al. 2018, which formally replicates our findings. This analysis by the program STRUCTURE assumes the existence of “clusters” that can correspond to ancestry differences within the dataset under analysis. “K” here corresponds to the number of clusters in each run, and the populations under review represent most of the distinct Jewish communities today. The blue cluster corresponds to Ashkenazi ancestry, as we see it peaking in virtually all Ashkenazi Jews.

There’s tons of interesting stuff to notice here, but in the context of Eastern Sephardim, it’s most relevant to look at the results of the BulgarianJ and TurkishJ populations. We can see that even in K=2, where only “Ashkenazi” and “non-Ashkenazi” clusters are detected, these populations have high membership in the “Ashkenazi” cluster, with Bulgarian Jews having more than Turkish Jews, on average. Even as K increases, the blue cluster remains elevated in these two populations. We can thus be confident that Eastern Sephardim Jews have a significant component of their ancestry deriving from Ashkenazi Jews.

How can Eastern Sephardic Jews have such a large portion of their total ancestry derive from Ashkenazi Jews, and still be Sephardic Jews? How Sephardic are they really?

Well, it turns out even less than we might think. Formation of the new communities in the Ottoman Empire was complex, and not many people know that Sephardic Jews weren’t the only Jewish exiles heading to places like Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, and that there were also whole Jewish communities already living in these places before any of the exiles even arrived.

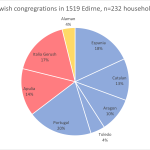

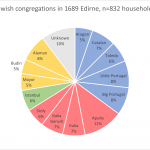

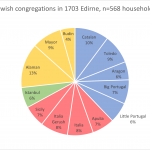

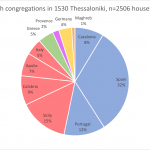

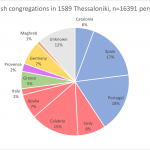

Historical sources help to reveal this history, forgotten behind the “1492 expulsion meme”. Yaron Ben Naeh’s Jews in the Realm of the Sultan explains how complex this history is. They reveal that Jews from Southern Italy– one of the most populous Jewish communities of the medieval world– were also expelled from their homeland region in a similarly dramatic fashion, with most exiles traveling to the Ottoman Empire. In addition, we learn about the local Romaniote Jewish communities, descending from Jews who had resided in Greece and Turkey for centuries. Both of these communities came together with Sephardic exiles and Ashkenazi migrants to form the bulk of Eastern Sephardim ancestry. See below for congregation census records from the 16th-18th centuries for Edirne in Bulgaria and Thessaloniki in Greece which reveal much of Eastern Sephardic Jewish ancestry. Blue highlight denotes Iberian Jewish congregations, Red denotes Southern Italian Jewish congregations, Greece denotes Romaniote Jewish congregations, and Yellow denotes Ashkenazi Jewish congregations. Unknown congregations are usually mixed. Thanks to a fellow hobbyist researcher and friend of mine for collecting and sorting this data!

As we can see, Eastern Sephardic Jews have significant ancestry from Jewish exiles from Iberia. However, this component is just one of several that sum up to their total ancestry. For most individuals it probably is not even the majority, with the Southern Italian Jewish and Ashkenazi Jewish components also being quite significant. During the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries, the Southern Italian Jewish congregations especially lost most of their following, with the Sephardic congregations growing in size. We can make sense of this by understanding the Sephardic Jews in these places as acculturating other Jews into their rite, which explains the near-ubiquity of Sephardic identity from this region despite their mixed ancestry. Most lay people as well as many scholars of Jewish history and genetics do not appreciate this fact and treat Eastern Sephardim as if we can assume they are near full descendants of Sephardic exiles. It seems clear to me that if we’re looking for the the highest proportion of ancestry coming from Sephardic exiles in population populations today, we shouldn’t be looking in the former Ottoman Empire. As mentioned above, I hold the communities deriving from the northern region of Morocco as the likeliest bastions of this kind of ancestry alive today.

We can also speak to crypto-Jewish communities in the mountainous border region of Spain and Portugal, such as from the Belmonte and Bragança districts, as well as the Chueta community of Mallorca, as also likely having a majority of their ancestry derive from real Sephardic Jews. However, these communities are very small, and individuals with full ancestry from them are very rare. Nevertheless, they’ve maintained a significant amount of Jewish ancestry through centuries of secrecy and persecution. We can also trace amounts of Sephardic ancestry being extremely widespread today, not only existing in small proportions among Ashkenazi Jews (<1%-3% of total ancestry) but also among modern Spaniards, Portuguese, and their descendants in Latin America. Sephardic ancestry definitely exists today, and we can use genetic techniques to infer details about it, but we still have a long way to go!

Again, please comment any questions, comments, or feedback you have. Hope you learned something and enjoyed!